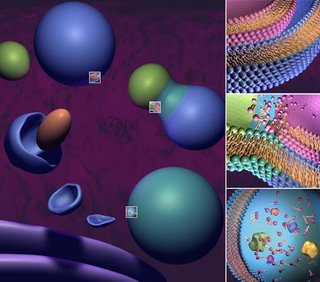

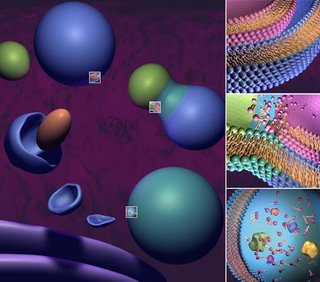

Figure 1. Cellular Autophagy

Figure 1. Cellular AutophagyIn an earlier post,

"Someone get a medievalist! Here Come the Morlocks!", Emile B. wrote, in relation to an ongoing discussion there [yet again!] on whether or not medieval studies can ever, really be ethical or political [or, let's say, whether or not medieval studies can really intervene, in an engaged way, with real-world social and political crises]:

It's not the performing of the ethical or the dislodging of prejudices that are problematic; it's rather the context in which these activities are undertaken that is troublesome. . . .

By "context," I mean not only the institution(s) but also the existential milieu(x), so that, in place of what Tillich calls "courage to be," critical medieval studies has degenerated into homogenous self-talk in the form of an auto-cannibalism consuming not only ideas and ever more words but possible futures, with all turned into one fecal paste. Mind you, not that I would be one to automatically dismiss fecal art.

As readers of this blog already know, BABEL's poet-jester Nelljean Rice, in her somewhat humorous

response to our recent roundtable sessions on "premodern to modern humanisms," raised this very point regarding what might be called the humanities' current state of auto-cannibalism. In fact, she practically encourages the notion, perhaps as a form of honesty, or at least as an implicit acknowledgement that part of what makes us human [and keeps us alive] is that we--both literally and figuratively--eat our own shit, and therefore, as she puts it, are also always "talking through mouthfuls of shit." And all this while, as Michael Calabrese eloquently states, life sometimes has a way of "cutting through" theory. But why do we always oppose "life" to "theory," especially when, it seems to me, so much of being human has to do with talking, talking, and more talking?

But this also raises for me [again] the specter of the hopeless chasm that supposedly marks off “life” from “what we do” [as literary scholars-philosophers] and “the real world” from the university [which is supposedly set apart and where, in the humanities at least, the main objective is in creating discourses about discourses of which the real world has no real need]. It’s just too convenient of a binary to evoke again and again—I mean, it’s all “life,” isn’t it, in one form or another? It’s all “real,” isn’t it? But it does, as Emile B. has pointed out numerous times, definitely have to do with context. Whatever it is you are doing in and with your intellectual work, where are you doing it and for whom or what purpose? These questions matter if you want to believe that your work should matter—to someone, somewhere, for some reason that might have something to do with the improvement of this thing we call “real life.”

It may be, though, that we should also embrace our irrelevance—all the ways in which the humanities have been decentered within the contemporary university, but also all the ways in which our so-called attention to the political dimensions of humanistsic subjects [whether literary texts or paintings, historical documents or symphonies] is only just that: an attention or regard, and not, in and of itself a political or ethical action that might, say, change or save or protect an actual human life. To call attention to the anti-Semitism of Chaucer’s “Prioress’s Tale,” or to the anti-Muslim perspective of “The Song of Roland,” or to all the ways in which history is manipulated by the victors—it’s altogether too easy, isn’t it, and even obvious? But that doesn’t mean this work shouldn’t be done—in teaching and in scholarship—only that we should be careful about the broad claims we might want to make for this work’s social or political impact beyond the setting of the university or all of the quiet places in which a scholar’s work is read and ruminated, here and there, places that number in the double digits [haha], unless that scholar is an Edward Said or Slavoj Zizek, but even then, would their readership rival all the fans who were crowded into the St. Louis Cardinals baseball stadium last night? But I like to think, too, that the humanities might matter most at the exact moment they are deemed “dead”—this is the moment at which we could reinvent ourselves as a “stealth humanism” that comes up from under, and never again “lectures” from above, where we recognize that we are guerilla artist-ethicists and not practitioners of a so-called “rational” science or philosophy.

Of course, history matters, and I think it would be unwise and unthrifty to rehash here and now all the reasons why it matters, to those who are dead but also living, although we might ponder all of the ways in which this becomes yet another academic argument that no one is really listening to. The biggest case in point [for me, anyway] on this subject is the Bush administration’s handling of so-called enemy combatant prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and elsewhere. A knowledge of the history of the rhetoric and practice of torture, from the classical period to Algeria, simply doesn’t factor in to their deliberations, actual practices, and after-the-fact justifications. They are not “humanists,” in the sense that they have likely not read and studied something like Sartre’s preface to Henri Alleg’s

La Question, where he wrote that, “The purpose of torture is not only to make a person talk, but to make him betray others. The victim must turn himself by his screams and by his submission into a lower animal, in the eyes of all and in his own eyes. His betrayal must destroy him and take away his human dignity. He who gives way under questioning is not only constrained from talking again, but is given a new status, that of a sub-man.” Further, the aim of torture “is to force from one tongue, amid its screams and its vomiting up of blood, the secret of everything. Senseless violence: whether the victim talks or whether he dies under his agony, the secret that he cannot tell is always somewhere else and out of reach. It is the executioner who becomes Sisyphus. If he puts the question at all, he will have to continue forever.” The Bush administration likely could not even begin to process the existential horror of this insight. And for all of Bush’s posturing that he recently read Camus’s

The Stranger, we know that even if he is really reading it, he is not understanding it, because he is not the good student in that sense, and he has no good teachers. In the meantime, in all the prison cells, men are literally losing their minds.

The Bush administration is also not likely going to watch Michael Haneke’s recent film

Cache, starring Juliette Binoche and Daniel Auteuil, which is a kind of moral parable about the ways in which Algeria remains in the French consciousness as a kind of moral stain and also as a barely repressed and unconfronted nightmare of the past. The main character, George, is, aptly enough, a literary critic who has devoted his life to reading books and conducting a public television talk show about books and writers. His life is apparently placid and untroubled, although he is so self-involved [or buried in his books or just distracted] he does not realize his wife is having an affair, but that, cleverly enough, is not what the movie is really about. It is about his inability and unwillingness to confront the past and the part he played, even just as a child, in France’s crimes against the Arab Algerians. Although the audience discovers what this is and even has to witness the horror of its lasting psychic effects in the suicide of one of the characters [who slits his throat in front of George], fittingly, both for the arc of the movie’s narrative, the truth of the present’s negation of the past [and therefore, of history], and the fact of the utter uselessness of literature as anything other than a panacea or hiding place, the movie simply ends with George taking a sleeping pill, drawing the curtains in his bedroom, and going to sleep. No one ever really learns anything that can’t also be willfully forgotten and people continue to suffer.

What’s a medievalist to do? Perhaps acknowledge the fact that our work can never really be political in the sense that it could affect the decision of a legislature or a president or a populace, and also, perhaps, commit ourselves to the idea that we are not so much the custodians of a certain history as we are the chief worriers of historical memory who, in our recognition and resulting anxiety that we cannot do enough justice to the past—which is always too unfinished and not mourned enough—undertake a labor of creatively staged encounters with that past [mainly in writing] in order to reenact, over and over again, what Louise Fradenburg has termed the ethical crisis that always attends mourning: It is the same crisis “that attends creation in general, including the production of art, of the aestheticized as well as mnemomic signifier.” Further,

“It is when we are most anxious to preserve the past that we know we have not done justice and cannot properly ‘speak of them.’ To speak of them seems to set aside their set-apartness. Yet we cannot not speak of them, and also they cannot remain other to us, in part because of the mnemomic imperative of signification itself. We cannot not change them, because they do live on in us, and yet they cannot be changed, certainly their deadness cannot be changed, the life they lead now is not the life they once led. And yet they could not have led either life without the very vicissitudes of the signifier that produce this paradoxicality in the first place. The deadly or inhuman limit that is the Other, the unconscious, inhabits the living subject. We live in relation to the inanimacy of the signifier, and that is what we memorialize.” (Sacrifice Your Love: Psychoanalysis, Historicism, Chaucer, pp. 250-51)

As to paradox, it may be that part of our job is also to always be calling attention to it, not only because it is a spur to rethinking history, past and present, but also because it is a spur to lift ourselves out of our own complacency and disciplinary turgidity, which is everywhere around us. For myself, this past week, it has meant thinking about Stephanie Trigg’s cancer [the self-memorizing of which on her blog some will surely turn away from as “not academic” or “too personal for the chosen genre”], while also thinking about my own current intellectual labors over embodiment and Anglo-Saxon souls, the so-called end [or marginalization] of the humanities in the contemporary university, the impossibility, for all my bellowing to the contrary, that my work on Old English poetry could ever be truly, socially “relevant,” and the facts, stated in this week’s

New Yorker, that “Nearly half the people in the world don’t have the kind of clean water and sanitation services that were available two thousand years ago to the citizens of ancient Rome” and that “Half of the hospital beds on earth are occupied by people with an easily preventable waterborne disease” (Michael Specter, “The Last Drop,”

The New Yorker 23 Oct. 2006: 63). In what way are all of these things connected, or how do they cancel each other out? How, like W.G. Sebald [for me a kind of preeminent historian-as-artist], might I begin to “adhere to an exact historical perspective, in patiently engraving and linking together apparently disparate things in the manner of a still-life”? Ours is the humanistic labor against all of the falling asleep that is everywhere around us. It is also about consolation in the present, for the present, for ourselves. As to the future, it may never arrive.