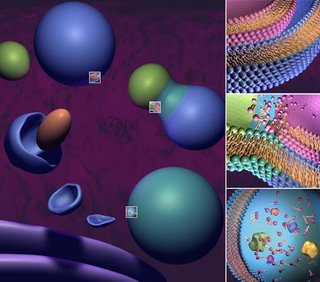

Figure 1. Cellular Autophagy

Figure 1. Cellular AutophagyIn an earlier post, "Someone get a medievalist! Here Come the Morlocks!", Emile B. wrote, in relation to an ongoing discussion there [yet again!] on whether or not medieval studies can ever, really be ethical or political [or, let's say, whether or not medieval studies can really intervene, in an engaged way, with real-world social and political crises]:

It's not the performing of the ethical or the dislodging of prejudices that are problematic; it's rather the context in which these activities are undertaken that is troublesome. . . .As readers of this blog already know, BABEL's poet-jester Nelljean Rice, in her somewhat humorous response to our recent roundtable sessions on "premodern to modern humanisms," raised this very point regarding what might be called the humanities' current state of auto-cannibalism. In fact, she practically encourages the notion, perhaps as a form of honesty, or at least as an implicit acknowledgement that part of what makes us human [and keeps us alive] is that we--both literally and figuratively--eat our own shit, and therefore, as she puts it, are also always "talking through mouthfuls of shit." And all this while, as Michael Calabrese eloquently states, life sometimes has a way of "cutting through" theory. But why do we always oppose "life" to "theory," especially when, it seems to me, so much of being human has to do with talking, talking, and more talking?

By "context," I mean not only the institution(s) but also the existential milieu(x), so that, in place of what Tillich calls "courage to be," critical medieval studies has degenerated into homogenous self-talk in the form of an auto-cannibalism consuming not only ideas and ever more words but possible futures, with all turned into one fecal paste. Mind you, not that I would be one to automatically dismiss fecal art.

But this also raises for me [again] the specter of the hopeless chasm that supposedly marks off “life” from “what we do” [as literary scholars-philosophers] and “the real world” from the university [which is supposedly set apart and where, in the humanities at least, the main objective is in creating discourses about discourses of which the real world has no real need]. It’s just too convenient of a binary to evoke again and again—I mean, it’s all “life,” isn’t it, in one form or another? It’s all “real,” isn’t it? But it does, as Emile B. has pointed out numerous times, definitely have to do with context. Whatever it is you are doing in and with your intellectual work, where are you doing it and for whom or what purpose? These questions matter if you want to believe that your work should matter—to someone, somewhere, for some reason that might have something to do with the improvement of this thing we call “real life.”

It may be, though, that we should also embrace our irrelevance—all the ways in which the humanities have been decentered within the contemporary university, but also all the ways in which our so-called attention to the political dimensions of humanistsic subjects [whether literary texts or paintings, historical documents or symphonies] is only just that: an attention or regard, and not, in and of itself a political or ethical action that might, say, change or save or protect an actual human life. To call attention to the anti-Semitism of Chaucer’s “Prioress’s Tale,” or to the anti-Muslim perspective of “The Song of Roland,” or to all the ways in which history is manipulated by the victors—it’s altogether too easy, isn’t it, and even obvious? But that doesn’t mean this work shouldn’t be done—in teaching and in scholarship—only that we should be careful about the broad claims we might want to make for this work’s social or political impact beyond the setting of the university or all of the quiet places in which a scholar’s work is read and ruminated, here and there, places that number in the double digits [haha], unless that scholar is an Edward Said or Slavoj Zizek, but even then, would their readership rival all the fans who were crowded into the St. Louis Cardinals baseball stadium last night? But I like to think, too, that the humanities might matter most at the exact moment they are deemed “dead”—this is the moment at which we could reinvent ourselves as a “stealth humanism” that comes up from under, and never again “lectures” from above, where we recognize that we are guerilla artist-ethicists and not practitioners of a so-called “rational” science or philosophy.

Of course, history matters, and I think it would be unwise and unthrifty to rehash here and now all the reasons why it matters, to those who are dead but also living, although we might ponder all of the ways in which this becomes yet another academic argument that no one is really listening to. The biggest case in point [for me, anyway] on this subject is the Bush administration’s handling of so-called enemy combatant prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and elsewhere. A knowledge of the history of the rhetoric and practice of torture, from the classical period to Algeria, simply doesn’t factor in to their deliberations, actual practices, and after-the-fact justifications. They are not “humanists,” in the sense that they have likely not read and studied something like Sartre’s preface to Henri Alleg’s La Question, where he wrote that, “The purpose of torture is not only to make a person talk, but to make him betray others. The victim must turn himself by his screams and by his submission into a lower animal, in the eyes of all and in his own eyes. His betrayal must destroy him and take away his human dignity. He who gives way under questioning is not only constrained from talking again, but is given a new status, that of a sub-man.” Further, the aim of torture “is to force from one tongue, amid its screams and its vomiting up of blood, the secret of everything. Senseless violence: whether the victim talks or whether he dies under his agony, the secret that he cannot tell is always somewhere else and out of reach. It is the executioner who becomes Sisyphus. If he puts the question at all, he will have to continue forever.” The Bush administration likely could not even begin to process the existential horror of this insight. And for all of Bush’s posturing that he recently read Camus’s The Stranger, we know that even if he is really reading it, he is not understanding it, because he is not the good student in that sense, and he has no good teachers. In the meantime, in all the prison cells, men are literally losing their minds.

The Bush administration is also not likely going to watch Michael Haneke’s recent film Cache, starring Juliette Binoche and Daniel Auteuil, which is a kind of moral parable about the ways in which Algeria remains in the French consciousness as a kind of moral stain and also as a barely repressed and unconfronted nightmare of the past. The main character, George, is, aptly enough, a literary critic who has devoted his life to reading books and conducting a public television talk show about books and writers. His life is apparently placid and untroubled, although he is so self-involved [or buried in his books or just distracted] he does not realize his wife is having an affair, but that, cleverly enough, is not what the movie is really about. It is about his inability and unwillingness to confront the past and the part he played, even just as a child, in France’s crimes against the Arab Algerians. Although the audience discovers what this is and even has to witness the horror of its lasting psychic effects in the suicide of one of the characters [who slits his throat in front of George], fittingly, both for the arc of the movie’s narrative, the truth of the present’s negation of the past [and therefore, of history], and the fact of the utter uselessness of literature as anything other than a panacea or hiding place, the movie simply ends with George taking a sleeping pill, drawing the curtains in his bedroom, and going to sleep. No one ever really learns anything that can’t also be willfully forgotten and people continue to suffer.

What’s a medievalist to do? Perhaps acknowledge the fact that our work can never really be political in the sense that it could affect the decision of a legislature or a president or a populace, and also, perhaps, commit ourselves to the idea that we are not so much the custodians of a certain history as we are the chief worriers of historical memory who, in our recognition and resulting anxiety that we cannot do enough justice to the past—which is always too unfinished and not mourned enough—undertake a labor of creatively staged encounters with that past [mainly in writing] in order to reenact, over and over again, what Louise Fradenburg has termed the ethical crisis that always attends mourning: It is the same crisis “that attends creation in general, including the production of art, of the aestheticized as well as mnemomic signifier.” Further,

“It is when we are most anxious to preserve the past that we know we have not done justice and cannot properly ‘speak of them.’ To speak of them seems to set aside their set-apartness. Yet we cannot not speak of them, and also they cannot remain other to us, in part because of the mnemomic imperative of signification itself. We cannot not change them, because they do live on in us, and yet they cannot be changed, certainly their deadness cannot be changed, the life they lead now is not the life they once led. And yet they could not have led either life without the very vicissitudes of the signifier that produce this paradoxicality in the first place. The deadly or inhuman limit that is the Other, the unconscious, inhabits the living subject. We live in relation to the inanimacy of the signifier, and that is what we memorialize.” (Sacrifice Your Love: Psychoanalysis, Historicism, Chaucer, pp. 250-51)As to paradox, it may be that part of our job is also to always be calling attention to it, not only because it is a spur to rethinking history, past and present, but also because it is a spur to lift ourselves out of our own complacency and disciplinary turgidity, which is everywhere around us. For myself, this past week, it has meant thinking about Stephanie Trigg’s cancer [the self-memorizing of which on her blog some will surely turn away from as “not academic” or “too personal for the chosen genre”], while also thinking about my own current intellectual labors over embodiment and Anglo-Saxon souls, the so-called end [or marginalization] of the humanities in the contemporary university, the impossibility, for all my bellowing to the contrary, that my work on Old English poetry could ever be truly, socially “relevant,” and the facts, stated in this week’s New Yorker, that “Nearly half the people in the world don’t have the kind of clean water and sanitation services that were available two thousand years ago to the citizens of ancient Rome” and that “Half of the hospital beds on earth are occupied by people with an easily preventable waterborne disease” (Michael Specter, “The Last Drop,” The New Yorker 23 Oct. 2006: 63). In what way are all of these things connected, or how do they cancel each other out? How, like W.G. Sebald [for me a kind of preeminent historian-as-artist], might I begin to “adhere to an exact historical perspective, in patiently engraving and linking together apparently disparate things in the manner of a still-life”? Ours is the humanistic labor against all of the falling asleep that is everywhere around us. It is also about consolation in the present, for the present, for ourselves. As to the future, it may never arrive.

Hehehe. I doubt you really love your irrelevance, EJ.

ReplyDeleteI said before that I think binaries are incredibly useful for thinking. Do they describe reality in its plenitude, e.g., is the opposition theory and life any sort of a full description of human existence? I should think not. But we do we make choices. We make choices when we compose job advertisements that seek, in the name of an entire academic department, a Doppelganger. Those choices I find repugnant. They typify the narcisisstic enclosure that is one of the things, if not the chief thing, that perpetuates the sterility of purely academic endeavors, and not just in medieval studies obviously. They are what ultimately guarantees that the words certain kinds of academics produce will never transcend “teleological thinking” in Ricketts’s sense.

This is not good humanism, EJ. Humanism cannot entail an embracing of irrelevance. To declare oneself irrelevant or, worse, to act as though one were irrelevant strips persons of their humanity by foreclosing what I consider to be one of humanity’s basic needs: namely, to be related to others fully. Insanity, as Fromm described it certainly, is precisely that condition in humans in which they have lost the capacity to relate themselves. The Ouroboros does not relate itself to others. It is a poor symbol of the intermediate, since the intermediate is a field of openness, of opportunity, of potentiality. You deny the future and the possible when you eat your own tail. Declaring the “paradoxicality” of the signifier, as Fradenburg does, in order to make an obvious point about the past, the inhuman, the other always already inhabiting present humanity is more caudal consumption.

Just a short note [for now]: I did not mean that I was actually embracing the idea [or fact] of my irrelevance as a scholar-teacher of medieval studies; I only meant to say that the action of others declaring what I do to be irrelevant--academically, socially, or otherwise--might open up that space of indeterminancy you describe as a place within which new [and perhaps more honest] strivings toward relevancy could be accomplished. Obviously I believe in human-to-human contact as an important part of what I do [or want to do]. What I was trying to say by ending with the Sebald quotation and the idea of paradox was that, more than anything else, I would like to figure out ways to connect/stitch things together, into beautiful forms, even [as sites of wonder which then could trigger, let's say, affective attachment and ethical action], as opposed to just accepting that whatever I do, somewhere else, something else is canceling out what I do, or want to do, or say.

ReplyDeleteI see your intent now.

ReplyDeleteI not sure that, for me, the stakes ever involved relevancy so much as (to state it negatively) not persisting in the ethically bankrupt, inept, and/or complacent.

Certainly, your projects and your desire to use your positions (in the academy, in Babel, etc.) for the creation of something new & good are not irrelevant and, more importantly, are not complacent or bankrupt.

The people who need the real shaking up are those who have post-tenure slumbered. I cannot see EJ slumbering, ever.

Briefly, what worries me about "relevance" and "life cutting through theory" is that what these calls reduce to are not not life but death--of dignity, of pleasure, of thought, of the body. These are the most authentic things, yeah? You might add love to my list of authentic things, but "life" has a way of cutting through that, too. If we are thought to live most thoroughly when we know that in the midst of life we are in death, etc., then I'm dubious about, of course, about theory, literature, and the whole endeavor, life, whatever that is, included. I don't think that's what I should want.

ReplyDelete(Doppleganger thing: announcement should not be compared to the medievalist only but to the whole department and its interests)

Karl:

ReplyDeleteThe ad seeks a Doppelganger of one of the department's members. And does so virtually book by book. My point about narcissistic enclosure stands. As does my point about choices: someone wrote it (maybe it was written by committee, but I doubt it; even so, the entire department did not have hands in its composition), and someone approved it before it went out. But your fundamental point is right: of course the ad has the effect of speaking for the department and its "interests." Multi-layered narcissism is precisely what one expects in any bureacracy where the stakes are so low to begin with.

Elaborate on your problem with life cutting through theory. I'm caught on the double negative in the first sentence, and don't want to misconstrue you. Explain how there is a reduction to death. Thanks.

I love Emile's Doppelganger line, with its vast overestimation of the ambit of my research and publication. If only!

ReplyDeleteKarl is correct, though: what we are seeking is a medievalist who intensifies the strengths of our medieval/early modern program as a whole, and not some little scholar who mimics the lonely interests of its current medievalist. It'd be great to get someone who brings us in some wholly new directions, but those are tough to articulate in advance. Some of the wording of the MLA ad is legalese (language on "basic" versus "preferred" qualifications was mandated by the university's legal office to make our sorting mechanism more transparent and place us in compliance with new federal legislation on academic job searches).

Oh yes, why did I say "little scholar"? Because imitators are always smaller than their originals, a la Mini Me. RIP, as well, Nelson de la Rosa. Eileen, add that to your evolutionist nightmares: the glitterati will certainly decrease in size as they begin to appear more and more indistinguishable from some single Ideal Form. The Morloks will either stamp them to oblivion or use them as puppets.

It'd be great to get someone who brings us in some wholly new directions, but those are tough to articulate in advance.

ReplyDeleteBring in the new, indeed.

Is it really that tough to compose a list of attributes/areas that might suggest that that is your intent or, should I say, the department's? Certainly if a list of "preferred qualifications" mirrors the career of a certain well-known medievalist, then the ad in fact falls short of indicating publicly that the department is seeking "wholly new directions."

I can only imagine the letters you'll get, as some poor newly-minted or about-to-be-minted PhD tries to convince the hiring committee that, no, really her work on Anglo-Saxon homiletics takes up "the complexities of identity in their relation to texts and writing" (from a non-Anglocentric point of view--I mean, that's a given).

I, too, am waiting to hear Karl's thoughts on death. [Inbetween grading stacks of short papers on "Titus Andronicus," which feels like death, but occasionally makes me laugh when a student misspells "Lucius" as "Lucious." Indeed, I wish there was someone lucious around at this very moment, but no, I'm stuck on a university campus, where no one is ever quite lucious enough. Consider this my mash note for the day.]

ReplyDeleteAnd another thing: a very interesting discussion has been unfolding on the Savage Minds blog that is really pertinent to what we have been discussing here over the past few days:

ReplyDeletehttp://savageminds.org/2006/10/20/verbal-privilege/

[Thanks to Betsy McCormick for the tip.]

Briefly, what worries me about "relevance" and "life cutting through theory" is that what these calls reduce to are not not life but death--of dignity, of pleasure, of thought, of the body.

ReplyDeleteDouble what? Goddammit. Think of it as a ME intensifier: He nevere yet no vileynye ne sayde.

I don't have time to do this properly, but I heard MC's comment of life cutting through theory as death cutting through theory, because what he went on to discuss was not life and its pleasures and communities and the discussion of literature and experience of love--that is, what can't be reduced to biological functions, what makes life worth living--but rather crime and the breakdown of the social order and the body through violence and social incoherence, viz., death. When people accuse other people of ignoring the important things, of leading frivolous lives, the accusations tend to congeal around two nodes: insufficient sacrifice (you're not working hard enough, you're enjoying yourself too much) and insufficient awareness of suffering (generally that of others but also your own potential suffering: e.g., if you're unwilling to give up your civil liberties or strip others of theirs, you're insufficiently attuned to terrorism, crime, etc.). I hear both of these as accusations of being insuffiently aware of death. The willfully irrelevant life may well be a resistance to death, then.

More to say later perhaps? Hope that's enough for now, and hope I'm saying something more than ars gratia artis.

I guess it's no mystery that I see the willfully irrelevant life as resistance to life, more specifically, relatedness. Rollo May never ceased to point out the antithesis of love is not hatred, but apathy.

ReplyDeleteI read MC's comments as about preserving a certain version of living that is predicated on not being open to assault. If there is a way to lead an irrelevant life that means one is truly unfindable as an object of potential violence and decrepitude, then, by all means, it must be revealed.

I took MC to be painting a picture of the troubled social context in which he lives (and, of course, not just he). Living in/on a real border necessitates approaches to life and death matters that exceed the limits of a well-mimiced theory. If academic cleverness can protect and enhance lives, I haven't seen the evidence.

I don't know if anyone jumped over to "Savage Minds" blog as I suggested, and/or followed some of the multiple threads that preceded that particular entry, but I will take a little risk, and re-quote here part of a poem, "North American Tim," by Adrienne Rich, that was posted there, and which is apropos, I think, to this conversation:

ReplyDeleteEverything we write

will be used against us

or against those we love.

These are the terms,

take them or leave them.

Poetry never stood a chance

of standing outside history.

One line typed twenty years ago

can be blazed on a wall in spraypaint

to glorify art as detachment

or torture of those we

did not love but also

did not want to kill

We move but our words stand

become responsible

for more than we intended

and this is verbal privilege.

The "torture of those we did not love but also did not want to kill" stands out to me, especially when I consider E.B.'s reference to Rollo May's idea that the antithesis of love is not hate, but apathy [or I would say, a lack of attention]. Of course, there is no way to attend to all of the suffering single-handedly, and I am glad that Karl pointed out,

"When people accuse other people of ignoring the important things, of leading frivolous lives, the accusations tend to congeal around two nodes: insufficient sacrifice (you're not working hard enough, you're enjoying yourself too much) and insufficient awareness of suffering (generally that of others but also your own potential suffering . . . )."

I was really struck when I heard the octogenarian poet Jack Gilbert [and author, most recently, of "Refusing Heaven"] interviewed on NPR earlier this past summer when he addressed the issue of human suffering and what he saw his role as a poet was in all that. He said something to the effect of it being sinful not to experience joy in the midst of suffering, even others' suffering, who are separate and apart from you--that, further, actively choosing a kind of joyful embrace with a world often given over to various global horrors was itself a kind of ethico-political act, and he saw his own life's work as an exercise in loving the world [hence the title of his book, "Refusing Heaven"]. For me, the ethical imperative has something to do with botH: attending to others who may be suffering, but also seeking pleasure and joy in worldly/human entities.

Still, E.B.'s point about M.C.'s point is an important one:

"Living in/on a real border [for M.C., that is L.A.] necessitates approaches to life and death matters that exceed the limits of a well-mimicked theory. If academic cleverness can protect and enhance lives, I haven't seen the evidence."

Do we fiddle while Rome burns? Is that it? As to all those bodies who are unprotected and subject to great harm at the hands of those who would do willful violence to them, there is no group of people--whether social workers, political activists, or humanists--who have ever curbed this dark aspect of our very human nature. Literature is a witness to this.

We move but our words stand

ReplyDeletebecome responsible

for more than we intended

It's funny, I reread those lines from Rich as quoted by Eileen just after reading this:

Wealth and violence seem to sustain us in this life, but after death they avail us nothing; on the contrary, the pursuit of letters brings us little exept dislike as long as we live, but once we are dead our fame is immortal. Like a last will and testament, what we have written down in black ink is only of importance when we ourselves no longer exist.

That's Gerald of Wales talking about a best case scenario for the textual artist. Gerald was not hopeful at all that the world he inhabited would be altered by the texts he composed, yet even as he made that world grow smaller and smaller around him he never stopped in his composition and amplification.

Do we fiddle while Rome burns? Is that it? As to all those bodies who are unprotected and subject to great harm at the hands of those who would do willful violence to them, there is no group of people--whether social workers, political activists, or humanists--who have ever curbed this dark aspect of our very human nature. Literature is a witness to this.

ReplyDeleteThis seems to assume that literature is 1) an adequate witness to this "dark aspect," and 2) the best (or at least one of the better witnesses) witness we have. Leaving aside the implicit defeatism in the above quote, I would argue against literature as witness on both accounts. I can think of multiple languages that are superior, ethically superior. But, more crucially, I would argue that more interpretations of literature are indeed forms of fiddling while the center burns.

Nevertheless, it's nice to just let Rich speak isn't it--without glossing, without comparison to Gerald of Wales?

I like the Gilbert you reference. I am reading Eigen's book on Ecstasy, which I highly, highly recommend to all.

I didn't mean for my last statement to be defeatist, per se, although I can see that it kind of is--if by "defeatist" what is meant is that I appear to be saying that the situation of the bad things people are willing to do to each other is hopeless and therefore why bother trying to actually help anyone, I think I'll read [or write] a book instead. I didn't mean THAT. What I did mean, though, is that I'm fairly convinced, from my study of history and my own life experiences and what I see when I look around the present world that there will never be a way to have, say, universal peace, and that there is likely no end to all the creative and inventive ways human beings are willing to harm each other. That's a damn fact. But, at the same time, it's amazing how much sheer beauty and love and self-sacrifice there is at the same time, and other things, too, like red wine, Paris, Paris Hilton, baseball, Pokemon, Sharon Stone, Elgar, Chaucer, barbecue potato chips, bourbon, orchids, smog--you get the picture. It's all bad and all good and every freaking thing inbetween. Personally, I try to mix it up and be as many places as I can be: the good, the bad, the ugly--the bedsides of the dying, the playpens of the polymorphous, the opium dens, the waiting rooms, the classrooms, the quiet studies, the bars, the streets, and so on and so forth.

ReplyDeleteAnd this brings me to, as always, E.B.'s more important argument: that literature [or writing about literature] can never be one of the better witnesses to this thing we call real life or this place we call the world, in all its messy variety, beauty and horror, but I just, I guess, disagree. Literature, and art more broadly, can be one of the most ethical witnesses of all, especially because it is often trying to trace, through various devices of fictionality, what is most real about what it means to be here, with each other, in this world. I just finished reading [and teaching] for the umpteenth time Tim O'Brien's "The Things They Carried," a book that purports to be a collection of short stories about the Vietnam War but which is, in fact, a kind of novel about the difficulty of trying to write "true" war stories, which can never be about "what really happened," but which are about something more ineffable--what happens to the human soul through and after death, and how the living who have spent too much time with death always have to reckon with that. [And yes, Karl, sometimes it is always about deat--the great social leveller.]

There's a great story in there that kind of illustrates why literature matters [and how sometimes, it matters so much that, when it isn't "true" enough, it can kill someone, and why that matters, too]. It's about a guy named Norman Bowker who, after the war, can't really get his life started. The story is about how he drives around this lake in Iowa one evening over and over and over again. He just keeps driving for no apparent purpose in one circular direction, all the while playing over and over again in his mind one particular night in Vietnam when he and his comrades [including O'Brien] had to camp out in a field that was actually a communal latrine [but they didn't know that]. Overnight, it rains, the river crests, and one guy actually drowns in the shit during a fire-fight with the enemy. Bowker can't get this night out of his mind--he asks O'Brien to write a story about it, so he can make sense of it, and so he can explain to anyone who will listen to him why it matters. O'Brien writes the story--about a guy named Bowker who keeps driving around a lake in Iowa after the war and can't get this night out of his mind and wishes he could tell his father or anyone about it--but of course O'Brien adds some fictional elements [in particular, a plot thread having to do with how Bowker could have saved the guy who drowned in the shit, but didn't], and Bowker doesn't like the story at all. In fact, he commits suicide shortly afterwards. It turns out that O'Brien was the one who was responsible for the death of the man who drowned in the shit that night. So, he tells the story three times in the book, each time differently. And in the end, the story ends up being about trying to tell the story the right way. I have had war veterans in my classes who have told me that they have never read anything like O'Brien's stories that capture what war is "really like" so well. This is one reason why literature matters. There is, I would argue, a kind of psychic healing that occurs when certain readers encounter O'Brien's stories. And for those of us who have never been to war, we know something about war that we could not access otherwise.

As to writing about literature, it is not enough to just throw O'Brien's book at a bunch of students, or even friends, and not talk about it at all. Literary scholarship, in a sense, I really believe, if practiced well and with an attention to ethical regard [and also with a healthy respect for all the ways in which the various products of our imagination matter--why else would psychoanalysts care about dreams?], is a kind of talking-through the work of art in order to better understand its effects--emotional, psychic, socio-cultural, historical, etc.--upon us, and why that might matter somehow in not only how we conduct our lives, but how we represent those lives to ourselves and to those we care for. When done well, it's a communal act, and never a singular one.

I'll be more specific, for those who are following along at home:

ReplyDeleteLiterature is perhaps the poorest witness to the failure to curb the dark side. Much more powerful are the lived experiences of those in pain & suffering on account of others and their dark sides. It is not insignificant that MC doesn't put into words the story he alludes to. The struggles of people whose lives never get turned into literature--that's where our ethics should be directed.

And so there is an ethical continuum. And on that continuum are the stories of those in the helping professions who work directly with those whose pain is attributable to others and their dark sides. At their best, these are phenomenologies of pain and, you guessed it, love. One thinks of Juan-David Nasio's Le Livre de la douleur et l'amour (1996), which, aside from being brilliant, is the most ethically rich study of pain (true passion, passio) that I know and, if I could confidently defend it as such, that was ever written. This book is not mere interpretation of affective states of the kind that are piling up by literature PhDs; it is testimony to the limits of human suffering and our abilities to make sense of it and, most importantly, to heal it. Read the story of Clemence (which opens the book), a woman who lost her child a few days after she gave birth, and then look me in the eye and tell me that a literary humanist could touch it.

Read the story of Clemence (which opens the book), a woman who lost her child a few days after she gave birth, and then look me in the eye and tell me that a literary humanist could touch it.

ReplyDeleteOK kids, is it just me, or do lines like this make anyone else chuckle?

I know, I know, it's dead baby. Nothing is sadder than a dead baby. And I know, I know, we are supposed to be awed into silence by this, the somber revelation of the Unutterably Doleful. In the face of this cadaver and this grieving mother, I think that I am supposed to look away from Emile's keen and penetrating eye, and admit the destitution of the literary humanist.

But perversely, I laugh. I think: Emile is throwing dead babies at us! And he is using them to enjoin us to silence. It's like the Nazi maneuver: nothing shuts down a conversation like the invocation of Hitler, just like you can't argue with baby corpses. Such swerves into blunt emotional response aim to deaden dialogue. I know they are intended to be grave beyond words. Yet my own response -- inappropriate, and no doubt shallow -- is to roll my eyes and say "Puh-leaze."

It is interesting to note the difference between EJ's and EB's comments in this post. The one is engaged, generous, a provocation to prolonged and open discussion; the other can sometimes invite further comment, but just as often attempts to police what is sayable, to shut down conversation rather than incite it (paradoxically, he does this by ... posting comments). EB possesses a solemnity that I don't doubt he feels entitled to; yet it comes across to me as enamored of its own presumed gravitas.

To be honest, for the most part I find EB's comments tedious. At their worst, they are self-aggrandizing and painfully bitter. They frequently have useful bibliography, but contentwise they tend towards the predictable and the fairly narrow. Sometimes they make me sad that a former friend and collaborator has become, at his worst, an internet troll.

Having said that, though, I must admit that I do read EB's comments -- sometimes because I do learn things from them, but more often because EJ has an amazing talent of turning them through her generous readings into something far richer than they initially appear to me.

I will freely admit that the failing may well be entirely mine. But, as EB astutley points out, I am simply a self-replicating narcissist who (among other crimes against humanity) ruins Adrienne Rich by quoting Gerald of Wales. I probably couldn't chew my way out of the hermeneutic circle that I'm trapped inside even if I were a Ouroboros masticating its caudal appendage.

Oh wait, I am an Ouroboros masticating its caudal appendage! (see EB's analysis, above).

I'm afraid I can't add much to this conversation (as am preparing to substitute teach a class at the moment)-- but two quick things.

ReplyDeletefirst, EJ: As to writing about literature, it is not enough to just throw O'Brien's book at a bunch of students, or even friends, and not talk about it at all. Literary scholarship, in a sense, I really believe, if practiced well and with an attention to ethical regard [and also with a healthy respect for all the ways in which the various products of our imagination matter--why else would psychoanalysts care about dreams?], is a kind of talking-through the work of art in order to better understand its effects--emotional, psychic, socio-cultural, historical, etc.--upon us, and why that might matter somehow in not only how we conduct our lives, but how we represent those lives to ourselves and to those we care for. When done well, it's a communal act, and never a singular one.

You touch, earlier in that comment, on O'Brien's own words -- "The way to tell a true war story is to just keep telling it." It's been ages since I read The Things They Carried but I still vividly remember it from my first year of college, when I rushed out to buy the book after reading the assigned stories from the professor.

The stories we tell, are the most basic tool humans use for understanding -- and learning to read those stories seems as though it can't be any less important. I feel a bit simplistic chiming in after all of this discussion, but isn't the point of teaching literature to produce good readers? To become good readers ourselves, so we can look at the discourses that obscure certain aspects (usually the unsavory ones) of our society and see through them? I'm not saying that this or that is more or less ethical, that's too big an argument for me -- rather, is it possible that teaching others to read, to interpret, to THINK is an important part of a cultural whole, the part that doesn't get weighed down by rhetoric but can see how discourse often shapes the way we see our lives? As for writing literary criticism, I'd imagine much of it isn't helpful. But the multiplicity of possible readings itself -- when done ethically, responsibly -- I'd imagine is illustrative of another diversity, that of humanity, and as Eileen said above, the idea that reading -- and literary scholarship is, finally about reading -- is a communal act, and never a singular one.

And, as an aside -- it's precisely the fact that you can read Adrienne Rich and see the connection to Gerald of Wales, JJC, that makes your thoughts so interesting -- and frankly, what makes them important. If you can't see the past as having a connection -- vital, alive, and ever changing -- to the present, then there isn't much point, now is there. I know you know this -- but I say it from my position as a student -- to make the point that it's the teachers who connect past and present in precisely that way that are most inspiring. But of course I've said multiple times that I'm with Forster on that one -- only connect.

And as for letting words--Rich's or anyone's--speak for themselves, is that once they lose their present-ness (i.e., outside the context in which Rich wrote them, or even after her death), there's a danger in their being co-opted, precisely that they may

become responsible

for more than we intended

Do they always need editorialization or criticism? No. But sometimes, a lack thereof can perpetuate cultural myths that are deeply harmful (and I'm thinking of the use of old english and norse mythologies in Germany in the early part of the last century).

And at this point, I should close and get back to reading for class.

JJC: It's not the dead babies that matter. You haven't read the story of Clemence, I see. If you had, you would see that it's the story of an analyst's quite amazing treatment of a woman who has lost a child. I should have been more specific or you more educated. I doubt even Nasio will awe you into silence. That's a shame. I can tell you that another reading of Gerald of Wales does not awe me either.

ReplyDeleteYour defensive laughter versus EJ's ability to open herself to my often blunt (by design) statements in this forum. EJ's struggles with the reasons, the real possible reasons, underlying the undertaking of a new/any scholarly project versus your self-content and self-referential empire-building. Emblazon the Ouroboros on your office door. Maybe you already have, and you think that is so ironic.

Internet troll? Hell, I've saved this blog from becoming an intellectual desert on multiple occasions.

I've saved this blog from becoming an intellectual desert on multiple occasions.

ReplyDeleteWhat's wrong with a desert? "The therapeutic dimension of the desert is one tied to its function as a space of radical potentiality, a place whose ultimate meaning is unfixable, unstillable"

I'm not going to get mixed up in this deeply. At this stage in my career, such as it is, too much self-doubt about the profession will snap me off at the ankles. I'm a medievalist because I'm not any good at anything else and because, so far, it's been a good way to get out of the morass of my family's small-minded, incurious assurance of the way things are.

But I have to respond to this:

To declare oneself irrelevant or, worse, to act as though one were irrelevant strips persons of their humanity by foreclosing what I consider to be one of humanity’s basic needs: namely, to be related to others fully.

When I say "irrelevant," I'm also saying "play," in the sense of looseness, of having a bit of give, but also in the sense of being in a space in which things, however temporarily, don't have to matter. That space gives us--or, at least it's given me--new purchase on the world. I'm about to teach the Franklin's Tale, and thank the ftm that I don't have to deal with its issues in "real life" (whatever that is, and I'm still convinced "real life" in most discussions = death). Maybe the FT will give my students or me a new route to some problems; maybe it won't. But I'm going to enjoy teaching it; I'm going to be, for a time, content and excited; I'm going to have a community with my students that should last 80 minutes or so, which is more than I get with 99% of the people I encounter. What's the point of anything without those moments?

And thank god for theory. Perhaps someone might say that by reading Butler or Marcuse's "Ideology of Death" or any of the many life-altering works I've stumbled upon or sought out, I'm getting things at an inauthentic remove from the people doing real work. Maybe. But what I've experienced isn't inauthentic, nor is it only career building. It's been of a real, indisputable value to me, and, I'd like to think, of value to my communities.

Thank you, Emile Blauche, for your rescue efforts. Without your moist -- err, I mean blunt -- words, this blog would no doubt turn as arid as the Sahara.

ReplyDeleteOr, then again, maybe not.

It seems to me that you have been provocative in very useful ways for Eileen. And, indeed, for Karl. That really shows their resourcefulness, and I admire them for it (among many other things). I admit, too, I've learned something from your posts. But many times they simply make me roll my eyes, or chuckle, or grow sad that you could remain so bitter about the profession that showed you to the door.

I don't doubt for a minute that you are a committed intellectual who cares very deeply about the issues you've posted upon. That apssion is evident in many comments. But you have also become the very thing that when I knew you way back when you would inveigh against: smug, self-enamored, puffed up by a sense of superiority.

And perhaps -- may I humbly suggest -- you are not nearly as godlike as you believe yourself to be in your ability to transform into fecund fields intellectual spaces that would otherwise dry to dust. "In the Middle" is a lively, communal project that did not in fact need rescuing at all.

Or, at least, I was happy with it. But then again we snakes who munch our own tails are easily pleased!

ReplyDeleteforeclosing what I consider to be one of humanity’s basic needs: namely, to be related to others fully.

ReplyDeleteFor example: Lacan's "Il n'y a pas de rapport sexuel." I was raised in a Fundy household, in a faith in which I was assured that if I didn't repent wholeheartedly, I was doomed. In effect, this faith--a version of pietism, I think--doomed me to an unending, impossible hunt for an authentic relationship with my Creator. It doomed me to find in myself an authentic love for the Jeebus that I could never have. I can't imagine all the multiple ways this emphasis on "full engagement" and "authenticity" fucked me up, but I'm sure it did. Lacan gave me the language to, well, traverse the fantasy, not to get out of it, but to know there's no way out, so, at least, I can put my efforts elsewhere.

Now the Franklin calls, and how.

Godlike? Nope. Again, you missed the point.

ReplyDeleteI don't hold my cards; I play them. If that is taken to be a sense of self-superiority, then so be it. We shall see how your anti-sentimentality argument holds up when you have the opportunity to say something off the cuff in May. And, please, do bring in the Nazis--that always lends an enormous credibility to one's critique.

You are eating your own words, JJC. You blast me for "dead babies" and then create a separate blog entry linking to the discussion? Who's being sensational? Or are you just being masochistic?

Karl: I am not anti-theory. Never will be. Theory use and theory reading are about context and choice. (Sorry, JJC, sometimes you have to repeat something until it sinks in.) (Not that in my "smug" way, I mean to suggest that Karl doesn't get it.)

Please could you provide 'spark notes' for 'In the Middle' some time? Coming to it in medias res, I realise I have missed the first act, don't know the characters and so don't follow the plot entirely.

ReplyDeleteMy reason for reading at all? Much of it is well written and as a non literary critic I have a serious fascination in what literary critics think it is that they do. Though I am not one of you - I think that I may ultimately be on your side.

Now this may have come over as characteristically blunt - and I don't really mean it to be. Just reminding you of others passing by on the ether ... interested ... but confused. I wonder how many of us there are?

Well, folks, that about brings out the worst in me.

ReplyDeleteI suppose you can't run a blog long without adding something to the comment thread that you wish you hadn't. Although I don't like the me they present, I won't go back and delete my intemperate words. I do wish, though, that I had not posted some of what I wrote in that little exchange with Emile (I also wish that he would not pepper the blog with disparaging remarks about me, or appoint himself its Messiah -- but those two actions are wholly in his own hands).

I'm sorry, too, that the prospect of leaving me speechless at K'zoo seems so appealing to him. As to me, I bear him no ill will. In fact I grieve a little for the loss of his friendship. I do wish that he would find a more affirmative outlet for his intellectual energies, and would encourage him to found a blog of his own rather than attempt to rescue this one. I'm not kidding, eitehr: I'd certainly read his blog; I know it would be smart.

What's wrong with a desert? "The therapeutic dimension of the desert is one tied to its function as a space of radical potentiality, a place whose ultimate meaning is unfixable, unstillable"

ReplyDeleteTouche, Karl. And I even saw the point of the saber coming.

And thanks for your honesty about the stage you find yourself in the career and your forthright self-assessment.

Oh, I still enveigh smugness, JJC. Hence, my comments about your narcisstic defenses.

Spark notes version for N50: Emile and I have known each since we competed for the same job in 1993. We have frequently collaborated. I will even say that I owe much of my intellectual formation to him ... for example, he was one of the first medievalists who could feed my passion for critics like Deleuze. There is much to praise in him -- and I don't just mean the fact that he is frighteningly smart, he possesses a keen social conscience.

ReplyDeleteHis blog posts have repeatedly confronted me with what I dislike about him as well, and I have been sorry to see the axe grinding ... but I do regret my harsh and (I admit ) haughty words. As I said, it is not the kind of medievalist/public intellectual/person I want to be.

Please--bring it on at the Zoo. Those who know me well know that the last thing I want is silence.

ReplyDeleteAs for intellectual outlets: I found them, but thanks for the half-hearted show of support.

The support was not half hearted. It was genuine.

ReplyDeleteI've deleted the front page link to this discussion. You are right, Emile: it was sensationalistic, and advanced nothing.

OK, that's it from me on this one. Whew!!

This thread should likely die its own quiet little death, while also lingering with us so that we can ruminate further in other times and places, but I would like to briefly re-quote Karl:

ReplyDelete"Maybe the FT [Chaucer's "Franklin's Tale"] will give my students or me a new route to some problems; maybe it won't. But I'm going to enjoy teaching it; I'm going to be, for a time, content and excited; I'm going to have a community with my students that should last 80 minutes or so, which is more than I get with 99% of the people I encounter. What's the point of anything without those moments?"

I think a lot [and I mean, A LOT] about what kind of "community" is supposedly being formed with my students in my classes. Often, I don't think it's a real community at all so much as it is a chaotic and impersonally formed assemblage of disparate persons with conflicting and only occasionally mutual desires and intentions. Take at least one session to set aside the text[s] under consideration, no matter what the course is, and ask the students to consider with you what it really means to be in that classroom together. Be very honest with them about your own desires and frustrations and ask them to share theirs [about the class, sure, but also about college in general and their lives outside of college even more so]. This isn't about the literature or other texts under consideration *at all* but about the question of what "being together" means, or might mean. I do this at least once a semester in all of my classes and it is always, for me, an important [while also discomfiting] moment, while at the same time, it does not necessarily advance the specific pedagogical aims of the course in question. It's kind of like where you stop the videotape and ask, "where am I, again" and "who are you?"

On another [albeit, brief] note, I regret some of the damning and unloving words exchanged recently on this thread, but despite that, want everyone to know how much I value the exchanges we have here, and also Emile B.'s nagging [and sure, sometimes hostile] questions. My favorite characters in literature are often the ones who ask the toughest questions while also inviting everyone's enmity at the same time [in various ways]. It takes some courage, although, to be sure, if bitterness about anything is the main motivation, it likely isn't worth the inveighing. But sometimes there are also good reasons to be bitter, or at least, angry as hell. I just don't ever want to be complacent.

Well, still knee-deep in "family matters," and shouldn't have even posted this, so, until tomorrow, best, Eileen.

At the risk of stirring dead embers back into a fire I don't want to reignite, I simply add that if what has been demonstrated in EB's remarks is courage, then like UD (my colleague at GW) I must confess that bravery makes me want to hurl. There isn't all that much which is truly courageous in what I've seen written (or, if there is, then I don't understand courage or bravery very well ... neither disagreement nor disparagement nor the emitting of gravitas rays are in themselves brave acts). If an act doesn't risk "any remotely conceivable negative consequences," how is it brave?

ReplyDeleteThere's a way in which EB's comments directed towards you, Eileen, have been prodding yet helpful. They make you think better; they engage; they ultimately build intellectual community. The ones towards me have tended to be obnoxious, sanctimonious, even dumb. I don't doubt that, as Emile has said, they were intended for my own good. But you know what? In general I am deeply suspicious of those who act for someone else's own good, because the narrative behind such altruism is usually far more complicated than simply A Good Soul at Work. Such would-be rescuers of the deluded from themselves tend to be those who describe themselves as brave, as necessary gadflies, as upholders of the Venerable Ideal ... and are exactly the kind of intellectuals I spent my early career attempting to flee.

OK, enough on that. Let me quote you, Eileen, on community: I think a lot [and I mean, A LOT] about what kind of "community" is supposedly being formed with my students in my classes. Often, I don't think it's a real community at all so much as it is a chaotic and impersonally formed assemblage of disparate persons with conflicting and only occasionally mutual desires and intentions. To which I say: amen. Thinking about and creating and rethinking community is my only job: as a teacher, as a father who is a member of a family, as a department chair, as a medievalist who has some say in the contours of the profession, as a blogger. All of these are communities that matter deeply to me. All of them make me think every day about tolerance, about forced or desired change, about inclusion, about commitment, about fostering, about excellence, about (yes) ethics. None of them are possible -- for me at least -- without a generosity of spirit, humility, and love.

So a last word: I am so frustrated and annoyed by EB because I realize I no longer understand him -- no longer comprehend the person he has become or perhaps always was and I didn't see -- and yet I still in fact care deeply for him. The opposite of love, I am told, is apathy, and I am very far from that.

I kind of wish *I* were a free radical.

ReplyDeleteThanks, EJ, for the clarification on bitterness as a motivating force. JJC has his own soothing story of why I would bother to condemn teleological thinking and ethical bankruptcy. His compulsion (at one time sympathetic, at another aggressive) to bring up the fact of my departure from the academy reveals just how that little narrative may be serving his purposes.

ReplyDeleteDon't buy it for a second, folks.

My desire to pull the tail out of the mouths of some benighted medievalists has almost everything to do with my hope for a better future, a future EJ might call humanistic, one that I would simply call human.