by EILEEN JOY

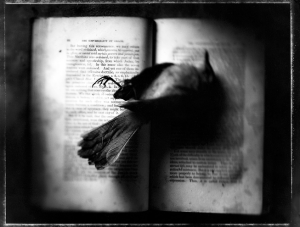

I submit to ink. I go into the

elsewhere of chiaroscuro. The lack of transparency, the elaboration of

shadow as a medium, makes the codex a soft bomb of potential. The

sociality of reading does not always or only pertain to the present; it

implicates the multi-temporal generosity of politics. Within this folded

time, the person and an impersonal speech test and inflect and mix into

one another. The book’s darkly confected scene is a speculative,

temporally striated polis.

As some of you may know, or as some of you may NOT know, the BABEL Working Group is moving its biennial meeting to odd-numbered years, starting in 2015, when we will be meeting at the University of Toronto, from October 9-11, under the banner, "Off the Books: Making, Breaking, Binding, Burning, Leaving, Gathering." We are pretty excited about this meeting, in no small measure because we've decided to let all potential session organizers decide what sort of structure(s) they might want for their sessions (duration-wise, format-wise, # of presenters-wise, setting-wise, etc.) and the programming committee will do their earnest best to pull these sessions together into a rowdy and invigorating un-conference stretching over 3 days. We are also going to experiment with how we structure the plenary [or un-plenary] sessions, so stay tuned on that! We have also worked really hard to construct a description of the conference's themes that both draws upon traditional manuscript and history of the book studies, and also examines various registers and valences of the phrase "off the books": how might we collectively explore various

histories of the book and bookmaking, as well as consider what it means

to go “off the books”: how ideas and various cultural and historical

forms leap off from and out of books; how we ourselves are “off of”

books and “over” books; what it means to go “off the books” or “off the

record”: to go astray, between and off the lines, underground, and

illegal, and to be unaccounted for. Going "off the books" thus means examining

books themselves—their place in our culture, social imaginary, sense of

history, and expectations of academic labor and value—while

simultaneously examining their edges, aporias, margins, lacunae, and

Others.

You can see the full Call for Sessions here --

-- and I will also repost it here:

4th Biennial Meeting of the BABEL Working Group

~ Off the Books: Making, Breaking, Binding, Burning, Leaving, Gathering ~

9-11 October 2015

University of Toronto, Canada

CALL FOR SESSIONS*

*Send session proposals of approx. 350-500 words (which can be completely

open to potential participants and/or already include some or all

committed participants), to include full contact information for

organizer(s) and any committed participants, NO LATER THAN February 1, 2015, to: babel.conference@gmail.com

For its 4th Biennial Meeting, to be held at the University of Toronto

from October 9-11, 2015, BABEL proposes to take flight both along and

off the fractal edges of

the book. As an institutional and

intellectual locus, the book has long occupied a privileged place as an

ultimate substrate and platform for the inscription and dissemination of

sustained thought and argument, of the images and ideas signified in

language, and of the cultural-historical “goods” of various groups,

societies and polities over time. Moreover, both the printed book and

manuscript hold a prominent place in the foundation of humanistic study

(think of how Homer’s corpus survives in the present thanks to its

translation

from papyrus to medieval manuscript “edition,”

or of the British Museum Library, founded in 1753, whose three founding

collections—donated by “mad hoarder” library- and cabinet-builders

Robert Cotton, Hans Sloane, and Robert Harley—have been instrumental in

the establishment of the study of English literature in the UK and North America,

and beyond). The book is not only an object, form, and genre, but also a

demand, a requirement, and a form of labor. It is the supposed monument

to tenure-worthy academic production (the monograph), as well as the

chief marker of communal academic and para-academic labors (edited

collections, art books,

climate change manga), and also a space of outright resistance to the status quo in

academic publishing and

beyond.

The book is also a symbol and reification of authority, canonicity, and

official terms, accounts, ledgers, and judgments. It is a location of

nostalgia, an affective touchstone for a past that maybe never was, that

also always remains entangled with the present of each book’s

production. The book is also

the chief exemplum of the print epoch

in the long history of media forms: the blank white page that waits

passively to be imprinted—impressed with/by—the works of human

subjectivity and intellectual-cultural production (but is this also a

mirage?). The book, further, signifies a certain

slow process

of cultural production, one that is often valued so highly precisely

because it is perceived as difficult, painstaking, voluminous, weighty,

and “serious”—the worthy achievement of a certain Olympiad-style

intellectual athleticism.

We are calling upon individuals and groups interested in proposing

sessions for our 2015 biennial meeting that would explore various

histories of the book and bookmaking, as well as consider what it means

to go “off the books”: how ideas and various cultural and historical

forms leap off from and out of books; how we ourselves are “off of”

books and “over” books; what it means to go “off the books” or “off the

record”: to go astray, between and off the lines, underground, and

illegal, and to be unaccounted for. Going off the books means examining

books themselves—their place in our culture, social imaginary, sense of

history, and expectations of academic labor and value—while

simultaneously examining their edges, aporias, margins, lacunae, and

Others. What might be potentialized, opened up, and

made when we break books, or break

with

books? Can we ever really leave books, or are we always somehow

interleaved—both in our solitary studies but also within our

University-at-large—with the books that have formed our education(s)?

Are there ways in which books themselves have provided spaces of

subterfuge, for going “outward bound” and “off the record,” for

resisting the business-as-usual of the Academy and other institutions?

Does going off the books, refusing to keep records, and shredding the

evidence-as-usual, while disseminating our ideas in other (

more supposedly radically “off-book” forms),

allow us to escape surveillance, or does it simply bind us to a surfeit

of labors that can never be properly compensated? Will we ever be able

to pay the price of our departure(s) from the forms of cultural capital

that have ensured so many programs of study, so many positions, so many

jobs? And why would we desire this path? We propose the sub-title

“making, breaking, binding, burning, leaving, gathering” as a set of

keywords (that are, importantly, also verbings and actions) with which

we challenge everyone to propose sessions that would investigate the

multiple trajectories and valences and entanglements of the past and

present of being both

bound to and

off the books.

Pre- and post-print media are “off the books” on either side. The

manuscript books that existed before and for a long time after the

invention of the printed “book” can be considered

pre- or peri- or proto-books,

not-books, un-books, books that shouldn’t be or that never were; they

are the messy material instantiations of the collected labor, texts,

thoughts, economies, ecologies and authorities of literary,

philosophical, and devotional production; they have been

made,

re-made, bound, unbound, stolen, modified, collected, decorated, cut

up, passed around, re-used, thrown away, burned, eaten by mold, worms

and critters, scraped, swaddled, broken and bequeathed. Scrolls,

rolls, booklets, tablets, quartos, charters, interlinear and marginal

commentaries, and various other “documents” are the (un/non)-books that

never were. So too digital media of various sorts are (un/non)-books

that never

were—instead of a unified, finite, and monolithic/monographic material presence,

their existence is diffused throughout the infrastructure of electronic media

and articulated for more or less fleeting periods on multi-purpose

surfaces; digital inscriptions and forms of dissemination show us the

limits of the book (material or not) even as they re-write and re-invent

it (and

digital forms of inscription themselves have limits that we wish to explore vis-a-vis the longer histories of “the book”).

Our current moment inspires and calls forth a whole set of questions relative to the past, present, and future of the book:

Is the digital age offing the book? Is the book merely dying on its own? Or being killed? Is it changing? Is it

now? Is it

then?

Is it alive? Is it zombified? Consider, for example, that among so many

“hard” media forms that have been introduced since the invention of the

printed book, only the book remains as a sort of durable

information/entertainment platform—as opposed to

celluloid film,

the phonograph record, the reel-to-reel tape, the 8-track tape, the VHS

tape, the cassette tape, the floppy disk, the hard- and zip- and

flash-drive, the CD, the DVD, and so on. If, while everything else (all

information, all “knowledge”) migrates to

the “cloud,”

the book persists, is this persistence perversely anomalous, or somehow

the natural result of a brilliantly built-in anti-obsolescence/

anti-cloud? What does it mean that the liveliness of books—if such can be argued for—is predicated upon

the use and objectification and even death of other beings:

animals, cotton plants, oak galls, geese, trees, etc.? Or upon the

nearly off-the-books subsistence wages of outsourced proofreaders and

warehouse workers (

Amazon’s “pickers,” for example)?

And what about the (often) unpaid labors of writers, editors,

booksellers, and publishers who continue to make and purvey books even

as they are declared “over” and “dead, whether for a certain fatalistic

love of something “old,”

a wild ambition to reboot a supposedly anachronistic form, the desire for a materially tactile instantiation of the imagination’s felicitous and promiscuous errancies, or for

the hope of a more robust public commons in which not just all ideas, but all

forms of the dissemination of those ideas, has equal purchase upon our collective attention?

Is the book more than an object-form? Is it also an ideal that

governs certain measures of scholarly production, now and in the past?

Is it magical, talismanic, more-than-human? Is it

a thing to be read, or a thing

reading? Is it an inscription, or an instantiation, or an incarnation? Is it even legible? What do we do with

unreadable, invisible, or impossible books?

Is “the book” singular or multiple? Is it disseminated, iterated,

copied, composed, collected, gathered, bound, and in what ways? Is it a

figure, a ground, a horizon? Is it a little world, made cunningly, or is

it utterly false: a cracked mirror, a bad representation of everything

it purports to “body forth”? Indeed, what sort of a body

is a book? What bodies does the book gather around itself, and in which times and places?

What sort of “gathering” (which is also a “thing”) is this?

“Off the Books,” as a conference-event, is also about more than

physical (or post-physical) “books” (delineated, perhaps overly

narrowly, as those objects we find on shelves in libraries that still

have shelves). In thinking outside the authorized, official, documented,

and on-the-record spaces of intellectual labor and production, we also

invite session proposals that consider what it means—emotionally,

ideologically, culturally, socially, institutionally, practically—to be

“off the books” of the university’s usual protocols, and off the books

of our disciplines’ usual methodologies, to be outside the parameters of

what is defined, recognized and rewarded in the current iteration(s) of

the Academy.

We

want to think carefully (and with a certain will to action) about the

growing body of contingent labor, unpaid labor, unacknowledged labor, precarious labor. We want to think about the university’s “books”—

its accounts, its records, its rules,

its protocols of oversight, and its production(s) of its own (often

oppressive and overly managerial-bureaucratic-technocratic) authority,

both within particular institutions (whether Harvard or the City

University of New York or wherever) and also within Western culture more

broadly. We also want to think about the erasures (

and the psycho-somatic violence)

often involved in the production of the Academy’s “official” records:

which bodies, agencies, agendas, accounts, motivations, ecologies, and

economies do the official documents cover up, suppress, oppress, or

exploit?

In thinking about being “off” the university’s books (its

ledger-keeping, its endless demands for assessment, its austerity

measures, its sorting mechanisms, its status-based hierarchies, etc.),

we therefore also want to consider forms of resistance that go “off the

[university’s regular] books,” about

undisciplined and undisciplinary labor, about so-called “academic” work that takes up residence in all the outré, dimly lit, queer “dives” of

the para- and non-Academy,

all the “come what may” places that flicker and shimmer in the spaces

of the in-between, the marginal, the gutter, the underground, the

temporary autonomous zones. How can we leave the standard “playbook” behind? How can we produce

subversive labors that allow us to gather together in gestures of

misfit future-izing, even while we risk censure, and maybe even our “careers,” while

also building new spaces for the

University-to-come?

How can we perpetuate and sustain the whisper networks that affirm the

validity and worth of the personal “account” and also construct more

durable architectures of heterotopic (dissensual) solidarity? How can we

bring bodies that have been historically suppressed and erased into

better focus and positions of self-empowerment and disturbing vocality

(“disturbing” because these voices thankfully, if distressingly, don’t

allow for self-assured complacency or banal forms of leftist liberal

pieties)?

“Off the books” is thus also meant to signify a collective

recognition of (and even an active, and not a passive, mourning for)

what never survived to make the leap from book to book to book to book

to book—papyrus, tablet, manuscript, print, digital—with a recognition

of what is not yet

in the book (recorded), but should or could

be. To feel that something is, and has been, “off the books” is a

condition of (a necessary) longing (or nervous angst) for the ways in

which that lost (and covered-over) past retains a kernel of something

that could still be realized (think:

Walter Benjamin’s idea

that those living in the past, who were the “losers” of history, are

turning by the dint of a secret heliotropism toward the sun that is

rising in the sky of history). Books contain, but they also include. The

canon is a problem only because of what it occludes (it

could contain, in Whitman’s parlance,

multitudes);

one response to judgmental and even accidental occlusions is a

radically promiscuous practice of inclusion. We might think, then, of

what has not yet been “on/in the books,” or what has only recently started to arrive in

some sort of “book” form

(if even as ancillary “data” or companion “environment”), or what kinds

of heretofore unanticipated “books” might be brought about by new

techniques, new translations, and new technologies. We might also think

about which books we wish had never arrived—books that we desire to

lose, unteach, forget, dismember, or relegate to the domain of bad

dreams.

We invite proposals for sessions that take us both “on” and “off”

books in any of the ways we have outlined, or in ways we have not yet

imagined. As with all BABEL endeavors, we invite and welcome

provocations that address and confront and work through questions,

issues, and subject areas we have not yet anticipated. Further, we

invite creative proposals for sessions from all academic fields and

sites of para-academic work.

Most importantly, this year we

launch a new conference (or un-conference) structure: instead of

determining in advance that sessions will be 90 minutes each, or 60

minutes each (as we have done in the past), we want YOU to propose the

session you

want to imagine, at the speed you want to run it:

for example, a “speed-dating” or “dork short” session, with 20+ people

circulating and doing 1-minute introductions of their research to one

another over the course of an hour or more; a seminar that meets for an

hour a day each of the 3 days; a 90-minute panel with three traditional

papers; an hour-long roundtable discussion with 5 or more persons

presenting research/ideas/writing relative to a specific topic or

question; a session that would take place over a brunch or lunch or

during the cocktail hour; seminar-workshops of 10 or more persons who

have circulated work and/or readings in advance; “flash-paper” sessions

where presenters have been given prompts in advance that they then

“respond” to in short (3-5-minute) performances; a session that extends

over the entire 3 days with some sort of performance or exhibit; a

“linked” session, spanning 2 hours with a break in-between, with

presentations in first half and “breakout” group discussions in the

second half; a “slow reading” session where 6+ people bring a passage,

an image, a text, an object, etc. which is then “chewed over/ruminated”

slowly with audience; a creatively designed “poster/object” session; an

anti-plenary plenary session; a “maker/making/unmaking” workshop/lab; a

session delivered entirely with emoticons; an intellectual “dim sum”

sessions that takes place over real “dim sum”; a session where people

give away work they will never be able to finish; etc., etc.

Think about sessions, too, in the form of: working group,

demonstration, performance, collision course, dramatic reading,

thought-experiment, dialogue, debate, seminar (with papers circulated in

advance), drinking game, diatribe, testimony, flash mob (or other type

of flash-event), roundtable discussion, complaint, drawing-room comedy,

speculation, gymnasium, protest, clinical trial, séance, laboratory,

masque, exhibition, recording session, screening, potlatch, cabinet,

slam, etc. In addition to calling for sessions that address books and

being “on” or “off” the books, we also invite sessions that are

themselves “off the books”—that is, off the record, secretive, hidden,

not conducted according to the usual protocols, or not institutional or

official in any way imaginable. We have set aside the following spaces: 2

rooms that can hold 50 people each; 1 room that can hold about 80; 1

seminar room that can hold 6-10; a hallway that can hold an exhibit, or

posters, or a small performance, or a very friendly flash mob; etc. If

you propose a session, and a time (preferably in half-hour increments),

we will work to make a schedule that will accommodate a lively, rowdy

multiplicity of sessions.

Please send session proposals of approx. 350-500 words (which can be

completely open to potential participants and/or already include some or

all committed participants), to include full contact information for

organizer(s) and any committed participants,

NO LATER THAN February 1, 2015, to: babel.conference@gmail.com.

BABEL@UToronto 2015 Programming Committee:

Suzanne Conklin Akbari (University of Toronto), Arthur Bahr (M.I.T.),

Roland Betancourt (University of California, Irvine), Liza Blake

(University of Toronto), Jen Boyle (Coastal Carolina University), Maura

Coughlin (Bryant University), Lowell Duckert (West Virginia University),

Irina Dumitrescu (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn),

Alexandra Gillespie (University of Toronto), Rick Godden (Tulane

University), Andrew Griffin (University of California, Santa Barbara),

David Hadbawnik (University at Buffalo, SUNY), Mary Kate Hurley (Ohio

University), Eileen A. Joy (BABEL Working Group), Dorothy Kim (Vassar

College), J. Allan Mitchell (University of Victoria), Susan Nakley (St.

Joseph’s College, NY), Julie Orlemanski (University of Chicago), Michael

O’Rourke (Independent Colleges, Dublin), Chris Piuma (University of

Toronto), Daniel C. Remein (University of Massachusetts, Boston), Arthur

J. Russell (Arizona State University), Myra Seaman (College of

Charleston), Angela Bennett Segler (New York University), Sean Smith

(Dept. of Biological Flow, Toronto), Karl Tobias Steel (Brooklyn

College), Cord Whitaker (Wellesley College), Maggie M. Williams (William

Paterson University), and Laura Yoder (New York University)

BABEL Future(s) Steering Committee:

Suzanne Conklin Akbari (University of Toronto), Liza Blake (University

of Toronto), Sakina Bryant (Sonoma State University), Jeffrey Jerome

Cohen (George Washington University), Lara Farina (West Virginia

University), Jonathan Hsy (George Washington University), Asa Simon

Mittman (California State University, Chico), Julie Orlemanski

(University of Chicago), Chris Piuma (University of Toronto), Angela

Bennett Segler (New York University), Karl Steel (Brooklyn College,

CUNY), and Maggie M. Williams (William Paterson University)

Here's a T-O Map from the Mandeville epitome that begins that famous fifteenth-century Carthusian miscellany, British Library Add 37049, f. 2v. (also famous for including the unique copy of the Middle English "Disputation between the Body and the Worms," which I write about here).

Here's a T-O Map from the Mandeville epitome that begins that famous fifteenth-century Carthusian miscellany, British Library Add 37049, f. 2v. (also famous for including the unique copy of the Middle English "Disputation between the Body and the Worms," which I write about here).